When is a bird not a bird? When an author turns it into something else.

As a child, I was envious of birds—they got to fly and I didn’t (although not for lack of trying. However, the less said about that, the better). Later on, during my Teenage Romantic Period, I idealized them as emblems of The Natural World, beautiful and perfect, training Wordsworth’s “cloud of glory.” Later still, I discover that what birds trail are lice, vermin, and some very nasty diseases. Science ruins another cherished illusion.

But not completely. Bluebirds, orioles, hummingbirds, even the despised pigeon—they still carry connotations that transcend those of us gravity-bound on Terra. Many authors have exploited this to create birds that are more than warm-blooded bipeds—birds with ambition. Here are five:

All The Birds in The Sky by Charlie Jane Anders

This novel, winner of the 2017 Nebula, defies classification. It’s a coming-of-age YA, it’s a dystopian cautionary tale, it’s a war between (and within) magic and science, it’s a love story, it’s genuinely strange in the best possible way. It’s also about birds, who here serve a dual function: They introduce the heroine to her magical powers as a future witch. They also act the traditional part of canaries in a coal mine, warning of eminent disaster, this time for the whole world. “Too late!” they cry, until the lovely writing and quirky inventiveness of Anders’s plot mitigate that to, “Almost too late. Practically too late.”

Never has a pigeon been so prescient.

Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick

Here birds not only know more than us, they are us. Or, at least, our replacements as the dominant and most intelligent species on a far-, far-future Earth. A time travel novel that scrupulously, and ingeniously, accounts for all the paradoxes of bouncing around through huge numbers of millennia, Bones of the Earth creates sentient bird-descendants that live in nests (and messy ones at that), have irritable personalities, and don’t think much of us, who didn’t use our regency over the Earth to much good effect. Birds as scolding Oxford dons.

Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton

Here it isn’t our bird-like descendants that drive the plot; it’s our birds’ ancestors. The connection to dinosaurs is made visual in the movie as the paleontologist Alan Grant arrives at and leaves behind the island, both times observing flocks of wheeling birds. However, the book also makes use of birds’ flocking behavior and DNA peculiarities in its fascinating discussions of genetics. Robin Redbreast, a bob-bob-bobbin’ along, was never like this.

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

Here birds serve a more traditional purpose, as symbols. Shevek, emissary from an ecologically austere but socially just world, has traveled to Urras, its exact opposite (and suspiciously like our Earth). When he first hears a bird singing in the garden, “a little, sweet, wild voice, a music in mid-air,” he is transfixed. Birds come to represent everything that his world does not have. Ultimately, this will lead to choices that determine the fates of two worlds.

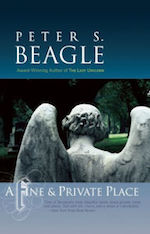

A Fine and Private Place by Peter S. Beagle

Many fantasies have birds as familiars to witches and wizards, but none are more appealing than Jonathan Rebeck’s raven. Rebeck, hiding from the world, has lived in a huge New York cemetery so long that he can see its ghosts. The raven brings him supplies and news. Sarcastic, compassionate, and hilarious, this unnamed raven has ambitions to save Rebeck from himself, an undertaking in which he aided by the indomitable widow Gertrude Klapper.

“There are people who give,” the raven says, “and there are people who take. There are people who create, people who destroy, and people who don’t do anything and drive the other two kinds crazy. It’s born in you, whether you give or take, and that’s the way you are. Ravens bring things to people. We’re like that. It’s our nature. We don’t like it. We’d much rather be eagles, or swans, or even one of those moronic robins, but we’re ravens and there you are.”

I think this is my favorite bird in all of literature. Yes. Definitely.

Nancy Kress’s SF has won six Nebulas, two Hugos, a Sturgeon, and the John W. Campbell Award. Her most recent book is Tomorrow’s Kin (Tor, July 2017), an expansion of the Nebula-winning novella “Yesterday’s Kin,” which takes the story forward several generations.

Nancy Kress’s SF has won six Nebulas, two Hugos, a Sturgeon, and the John W. Campbell Award. Her most recent book is Tomorrow’s Kin (Tor, July 2017), an expansion of the Nebula-winning novella “Yesterday’s Kin,” which takes the story forward several generations.